Over 100 US congressmen and women have called for an end to the criminal Cuba embargo. Ever wonder what it was like in Cuba before Castro got rid of the vultures who now live in Miami? Lets see:

In 1934 Fulgencio Batista took over the Cuban government in what became known as "The Revolt of the Sergeants." For the next twenty-five years he ruled Cuba with an iron fist, and the full blessing and endorsement of the United States government, who feared a social and economic revolution and saw him as a stabilizing force with respect for American interests.and...

Batista established lasting relationships with organized crime, and under his guardianship Havana became known as "the Latin Las Vegas." Meyer Lansky and other prominent gangsters were heavily invested in Havana, and politicians from Batista on down took their cut.

Through Lansky, the mafia knew they had a friend in Cuba. A summit at Havana's Hotel Nacional, with mobsters such as Frank Costello, Vito Genovese, Santo Trafficante Jr., Moe Dalitz and others, confirmed Luciano's authority over the U.S. mob, and coincided with Frank Sinatra's 1946 singing debut in Havana. It was here that Lansky gave permission to kill Bugsy Siegel.

Many of Batista's enemies faced the same fate as the ambitious Siegel. Nobody seemed to mention the many brutal human rights abuses that were a regular feature of Batista's private police force. Nobody, that is, except the many in Cuba who opposed the U.S.-friendly dictator.

At first the strong man made and broke Presidents: seven of them in seven years, including Grau San Martin, whom he propped up for a few months (September 1933-January 1934). He fattened the Army from 8,000 to 20,000 men, gave it one-fourth of Cuba's budget. He put down political unrest with a hard sergeant's hand.Lets not forget that most Cubans lived as peasants, little more than slaves, with no hope for themselves or their future. Castro changed all that, and very much for the better.

In the late '30s a change crept in. The dictator spoke of good dictatorship, "disciplined" democracy, constitutionality, economic reform. The cynical and the critical said that he talked big, did little to uplift Cuba's sugar-sick economy, uproot its age-old graft. But Batista began to curry civilian support. He encouraged opposition, pardoned political prisoners, even legalized the Communist Party. He cultivated culture. He took up smart squash-tennis (though he preferred cock-fighting), got a tailor, elbowed a way into Havana society, polished his pronunciation. He began to think of legitimizing his power. In 1940 he ran for the Presidency against his old revolutionary comrade, Grau San Martin. Batista won by a neat majority, which his opponents said was stacked by the Army.

Last year he told the politicians that they had better organize for the 1944 elections. They did not believe him until the President threatened to turn his job over to Senator Carlos Saladrigas if a new chief executive were not constitutionally elected. Then they tumbled into the arena.

New Man. The campaign was loud and ebullient, in the Cuban manner. Everyone admitted that cold, efficient Lawyer Carlos Saladrigas had no political appeal, but no one saw how he could lose. Gentle, starry-eyed Professor (of Anatomy) Grau San Martin supplied all the color, roused the mass enthusiasm.

In a soiled and wilted Panama suit, Dr. Grau stumped the countryside. The people remembered how, in his brief former Presidency during the great depression, he had tried to up wages, make more jobs. His earnest voice, his fervid sermons against corruption, his glowing talk of more schools and better roads, of Pan American solidarity and Cuba for the Cubans, sparked an emotional tinder. Peasant women knelt before him, held up their babies for his touch. Many believed the myth that "honest Grau" would end taxes, rent, electric and water bills.

When he cast his vote, Grau San Martin was sure that he would win if the poll was honest. He was as surprised as anyone over the result: the fairest, most orderly, least bloody (one death) election in Cuba's turbulent politics.

What Now? At 43, Cuba's strong man suddenly had new prestige. Fulgencio Batista was hardly ripe for retirement. He talked of a long trip among Cuba's neighbor countries; perhaps the ex-cane-chopper dreamed of becoming a voice in all Latin America. He was a man to watch. He was sure to keep one eye on the home island, to counter anything smacking of unpractical government. From his balcony last week he told his pueblo that if they ever needed him, he would answer their cries. Dr. Grau, preparing to move into the Presidential Palace next October, undoubtedly heard and pondered the outgoing dictator's promise.

12-Jun-1944. Time Magaine.

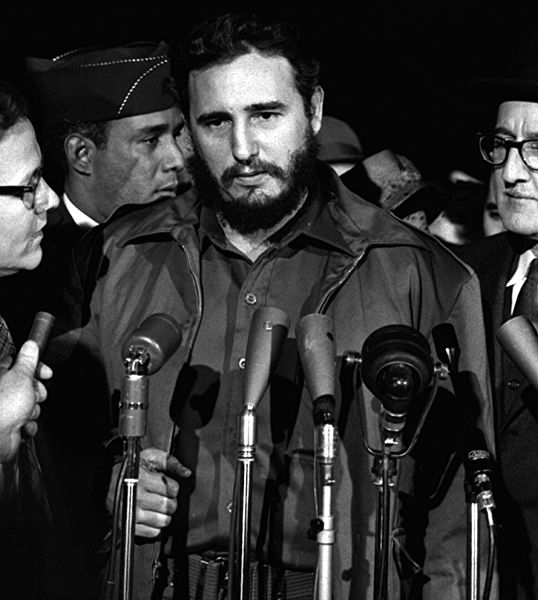

Praise for Fidel Castro from NYC Congressman Serrano:

Today’s news that Fidel Castro has retired from leading his nation proves yet again that this important figure defies the attempts of his critics to paint him simply as a power-hungry authoritarian. Instead, it proves that Castro sees clearly the long-term interests of the Cuban people and recognizes that they are best served by a carefully planned transition. Few leaders, having been on the front lines of history so long, would be able to voluntarily step aside in favor of a new, younger generation. In taking this action, Castro is ensuring that the changes he brought about will live on and grow.19-Feb-2008. New York Times.

I would like to congratulate both Fidel Castro and the Cuban people for this smooth transition of power. It is much to their credit that the much-predicted turmoil following Castro’s exit from direct control of the state did not happen. It proves that there is a broad base of support for the Cuban system on the island. It also proves that despite constant criticisms, Castro’s revolution was not merely a series of military events in Cuba in the late 1950s and early 1960s, but instead a process that continues to evolve in Cuba today.

As always, I want to take the opportunity to call on the Bush administration to change its backward and counterproductive policy of blockading and isolating the Cuban people. In a moment like this, it is wise to remember that the stated goal of the Bush administration and anti-Castro hardliners has been to push Fidel Castro from power. At times it seemed as though it was a personal grudge against Castro, remade into foreign policy. But now that he has voluntarily stepped aside and relinquished power, I wonder what twisted new rationale they will create to continue their failed policies. It is long past time to end the charade and begin dialogue and engagement with Cuba.

Our two peoples are so much alike, with so many shared linkages, it is particularly sad to see us continue to dwell on false and invented divisions. I deeply hope that the new leadership in Cuba can find a new opportunity for dialogue when a new administration comes to power in the United States in January 2009. It is time to recognize that Castro was a great leader for his people — and move toward engagement with his successor. It is time to put the past struggles behind us and move forward together.