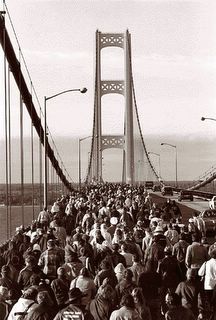

The Labor Day march across the Mackinac Bridge led by Michigan's governor. This photo comes from the Detroit News article "How Labor Won Its Day," which inspired the title of my blog. This is an abstract from that article (By Patricia K. Zacharias / The Detroit News):

History has almost forgotten Peter McGuire, an Irish-American cabinet maker and pioneer unionist who proposed a day dedicated to all who labor. Old records describe him as a red-headed, fiery, eloquent leader of the Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners.

McGuire introduced his idea formally at a meeting of the Central Labor Union on May 18,1882. "Let us have, a festive day during which a parade through the streets of the city would permit public tribute to American Industry," [my emphasis rir] he said.

The following September New York workers staged a parade up Broadway to Union Square. Few, if any, workers got the day off. Most were warned against marching in the parade with the threat of getting fired. Despite the warning, more than 10,000 workers showed up for the march. Led by mounted police, bricklayers in white aprons paraded with a band playing "Killarney." The marchers passed a reviewing stand crowded with Knights of Labor: a holiday was born. McGuire's holiday moved across the country as slowly as did recognition of the rights of the working man.

Twelve years later, on June 28, 1894, President Grover Cleveland, long a foe of organized labor, but under voter pressure, signed a Labor Day holiday bill. Earlier that same year, President Cleveland's most famous labor conflict, the Pullman strike in Chicago, had forced the president to call up federal troops. Employees of the Pullman Co., which produced sleeping cars for passenger trains, protested wage cuts. Led by Eugene V. Debs, the American Railway Union (ARU) in sympathy refused to haul railroad cars made by the company. A general railway strike ensued, interfering with mail delivery. When the ARU refused a court order to return to work, Cleveland sent in federal troops. "If it takes the entire army and navy of the United States to deliver a postal card in Chicago, that card will be delivered," he said. Rioting broke out: strikers were killed and leaders jailed, but even as the strike was broken, the labor movement gained steam [thereby forcing Cleveland's hand rir].

See the full article here.

No comments:

Post a Comment